Mark Zuckerberg can say whatever he wants. Llama models are not truly Open Source, at least not in the strictest sense of the definition. As explained by the Open Source Initiative, “Meta confuses ‘Open Source’ with ‘resources available to some users under certain conditions,’ which are two very different things.”

Please follow us on Twitter and Facebook

These comments, made after the release of Llama 2, also apply to Meta’s new family of generative AI models. In both cases, and across the industry, we see these models taking everything they can from the public internet (and likely some private sources as well) while using the term “Open Source” a bit too freely. Here’s why.

Infinite Voracity

Called Llama 3.1, these models show impressive performance and can even outperform GPT-4 or Claude 3.5. Mark Zuckerberg highlighted in an open letter how “Open Source AI is the way forward.”

The tweet with the image that Elon Musk posted a few months ago is no longer available on Twitter (X).

This is similar to what he said after presenting the models in an interview with Bloomberg. However, he did admit that Meta keeps the data sets used to train Llama 3.1 a secret.

“Although it is open, we are also designing this by ourselves,”

He said, mentioning that Facebook and Instagram posts, along with proprietary data sets licensed from others, were used, but without further details.

This lack of transparency is common in the industry. We don’t know exactly how other models like GPT-4 or Claude 3.5 were trained. It’s possible they used surprising data; for example, one dataset contained 5,000 “tokens” from my personal blog.

These models seem endlessly hungry for data. This has led to controversies, lawsuits, and agreements with content companies to license texts, images, and videos for training. Sometimes, they don’t even ask for permission. For example, OpenAI used a million hours of YouTube videos to train GPT-4.

“Open Weights” Is Not the Same as “Open Source”

It’s true that the model is freely available on GitHub, which is noteworthy. Like Llama 2, Llama 3.1 can be used by companies and independent developers to create models based on it. This is similar to how GNU/Linux distributions work, starting from a Linux kernel and adding their own elements.

The Llama 3 license allows this, but it also sets a key licensing barrier. Models derived from Llama 3.1 are free unless they become very successful. If the model is used by more than 700 million active users per month, a license must be purchased from Meta.

However, what Meta shares are the “weights,” which show how the model performs calculations. This lets anyone download the trained neural network files and use them directly or refine them for their own needs. This makes these models “Open Weights” rather than “Open Source.”

As Ars Technica explains, this is different from proprietary models like those from OpenAI, which do not share these weights and monetize their models through subscriptions to ChatGPT Plus or an API.

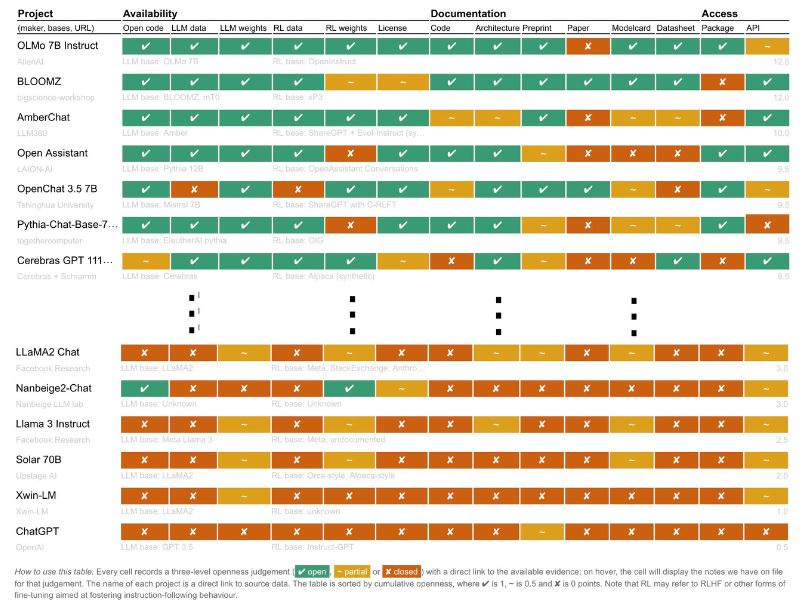

The term “open” used by many AI projects, including Llama 3.1, is facing increased scrutiny. An interesting study by Radboud University in Nijmegen, the Netherlands, assessed various AI models on parameters that determine how open they are.

The result is a table showing that no model is perfect in this regard. Meta’s models rank very low, making it hard to consider them truly Open Source. Simon Willison, co-creator of the Django programming environment and an expert in this field, commented that Mark Zuckerberg’s open letter was “fascinating” and “influential,” but also noted that:

“it seems, however, that we have lost the battle in terms of getting them to stop using the term Open Source incorrectly.”

Zuckerberg’s influence makes it hard for the public to recognize that Meta’s models are not fully open source.

As Willison said in comments on Ars Technica:

“I consider Zuck’s prominent misuse of ‘open source’ to be an act of cultural vandalism on a small scale. Open source should have a consensual meaning. Overusing the term weakens that meaning, which makes the term less useful overall. If someone says ‘it’s open source,’ that no longer tells me anything useful. And then I have to dig around and find out what they’re actually talking about.”

Indeed, this widespread use—by Zuckerberg and others—has weakened the concept. Part of the issue is that there is no universal, accepted definition of what open source means generally, and what an open source AI model is specifically.