Researchers at the University of Southern California conducted a simulation to study what happens when satellites burn up during re-entry. The results raise concerns about the long-term environmental impacts of large satellite constellations like Starlink.

Please follow us on Twitter and Facebook

The study, published in the journal Earth and Space Science, focuses on the aluminum content of satellites, which makes up about 30% of their mass. When these satellites enter the atmosphere at the end of their operational life, they undergo a process called thermal ablation that creates aluminum oxide nanoparticles.

Aluminium Oxide Nanoparticles in The Atmosphere

Researcher Dr Jane Smith explained:

“We found that these particles can remain in the upper atmosphere for decades before settling in the ozone layer. There they can then catalyse reactions that deplete the ozone.”

The team’s simulations showed that a typical 250 kg satellite could generate about 30 kg of alumina nanoparticles upon re-entry. This may not seem like much, but the cumulative effect of hundreds or thousands of satellites could be significant.

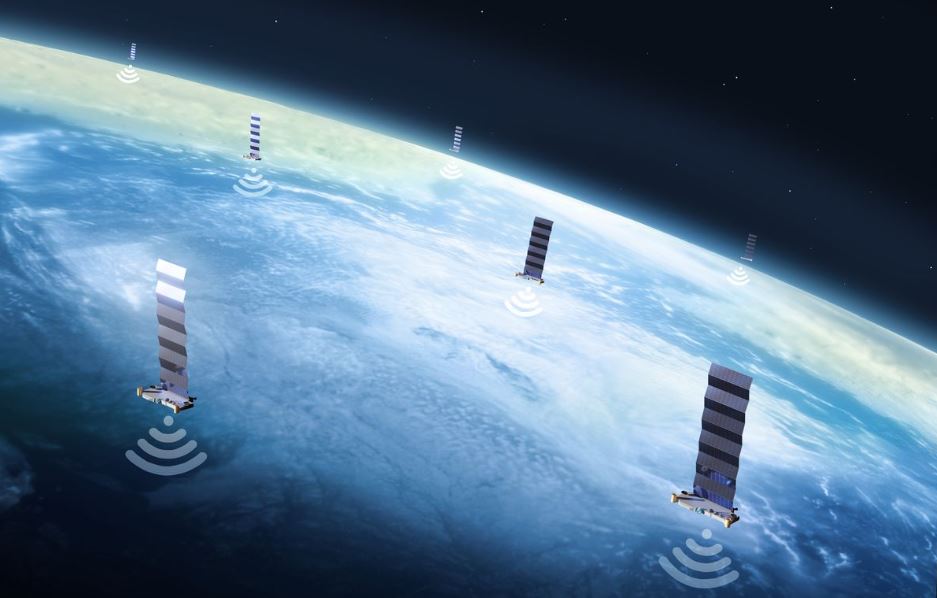

Mega Constellations Increase Concerns

The research comes at a time when several companies are planning to launch massive constellations of small satellites for global internet coverage and other services. These mega-constellations will dramatically increase the number of objects entering Earth’s atmosphere in the coming years.

Dr Smith explained:

“Our calculations suggest that by 2022, satellite crashes will already be releasing about 17 tonnes of aluminium oxide per year into the Earth’s atmosphere. In a future scenario with mega-constellations, this amount could rise to over 360 tonnes per year.”

Impact On the Ozone Layer

The study estimates that these human-caused inputs could exceed natural aluminum inputs from micrometeorites by more than 640 percent annually in the worst-case scenario. This significant increase in aluminum compounds in the upper atmosphere has unknown consequences for ozone chemistry and climate.

Dr. Mark Johnson, an environmental scientist not involved in the study, cautioned:

“While these results are worrying, we need further research to fully understand the impacts. The ozone layer has recovered from damage in the past, but we should not take this for granted.”

The research team emphasized that the study only considered the oxidation of aluminum and that several simplifying assumptions were made. It called for further research into the complex chemistry of satellite reentry and the potential environmental impacts.